Seventeen-year-old Mohammad Zubayer once dreamed of finishing school and getting a government job so he could help his Rohingya community in Myanmar’s Rakhine State.

But today he’s a refugee living in Bangladesh, where the government bars formal education in the crowded camps, leaving a generation of young people like Mohammad out of school and stuck in limbo.

"I wanted to be smart by studying,” said Mohammad, who completed the eighth grade in Myanmar before fleeing to Bangladesh last year. “I wanted to be a scholar to help the Rohingya community. But kids who want to study are not getting the chance."

Some 700,000 Rohingya refugees poured into Bangladesh after Myanmar's army launched a violent crackdown in northern Rakhine State last August following a series of attacks by a Rohingya rebel group.

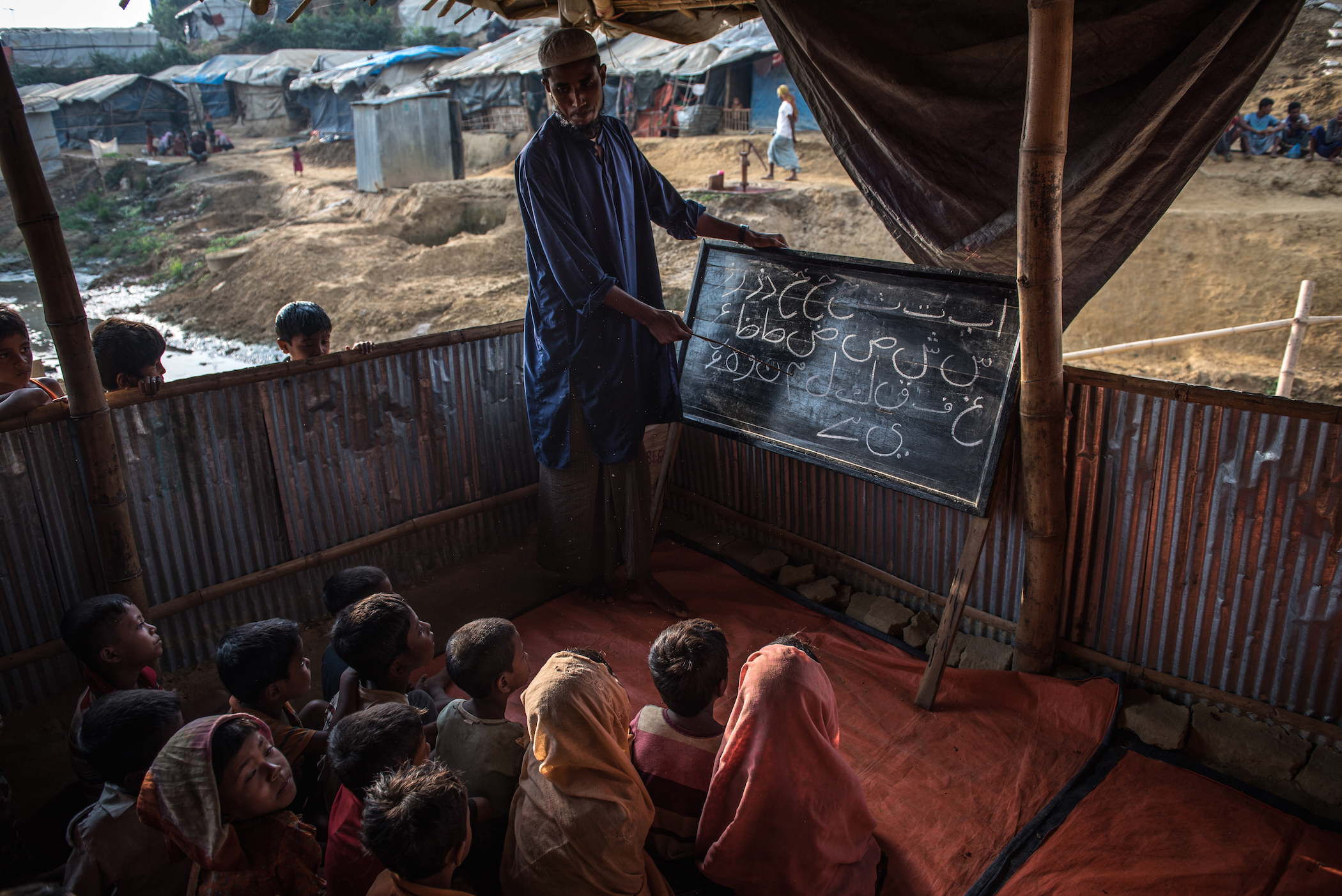

The Rohingya have found safety here, as well as food and healthcare. But formal education is out of reach for 530,000 school-age refugees, including the children of Rohingya who fled earlier waves of violence, because Bangladesh’s government does not want the Rohingya to stay long-term. Only a quarter of the school-age Rohingya have access to any kind of instruction, through informal classrooms set up in the camps – but even this is only for kids up to 14 years of age, and the level of the teaching itself doesn’t go past the second year of primary school.

The government of Myanmar, for its part, won’t allow its Burmese-language curriculum to be used in Bangladesh’s refugee camps. That means the same government responsible for forcing the Rohingya out of Myanmar has effectively blocked Rohingya children from continuing their education in exile.

"The next generation, they have no dreams,” said Serazul Mustafa, a refugee leader in Kutupalong camp, the largest in Bangladesh. “If you have graduated from fifth grade in Myanmar, you need to go to sixth grade. But there's no sixth grade, so what do we do? They can't continue their studies. They have no lives."

Without formal schools, "temporary learning centres" operated by NGOs like Save the Children and BRAC, a Bangladeshi aid group, allow some children to attend classes for about two hours per day, but there’s no certification to show they've completed a grade level.

The age and grade-level restrictions mean that the temporary centres aren't open to the majority of school-age Rohingya. Just one quarter of school-age youth – about 130,000 children – attend the classes, meaning that around 400,000 refugees who should be learning receive no education.

“They only educate the small kids,” said Kushida Begum, a refugee mother whose three children attended fourth, fifth, and sixth grades in Myanmar before the family fled to Bangladesh last year. “They say there is no school for big kids here. I am dying by thinking about the kids’ future.”

Mohammad Abul Kalam, who leads Bangladesh’s Office of the Refugee Relief and Repatriation Commission in Cox’s Bazar, said, “It is the general understanding within the government that Rohingya repatriation will begin soon, so formal schooling is not necessary [or] cost effective.”

But multiple waves of Rohingya have sought safe haven in Bangladesh over decades. A plan to begin sending recent refugees back to Myanmar fizzled earlier this year.

Kushida’s youngest, a daughter, has enrolled in one of the camp's learning centres, even though the classes are not advanced enough for her. The two older children, both boys, don’t attend classes.

"When I remember about the school [in Myanmar], I feel sad, because now I can’t study anymore," said Kushida’s younger son, Forizul. His brother, Mohammad, added, "Now we're just sitting and doing nothing."

Officials from Bangladesh's Ministry of Education did not respond to IRIN's emailed requests for interviews.

Tough start back home

In Myanmar, education was never a given for Rohingya children. Rohingya girls were often not sent to school, in part due to deep conservatism within the community. But apartheid-like restrictions imposed on the minority group meant all Rohingya children had spotty access to education. And once in school, Rohingya children reported discrimination from teachers and classmates of other ethnicities.

That means education levels among the Rohingya children attending the camps’ temporary classrooms vary greatly: for some young children, classes at the learning centres are the first education they've ever received. For others, like Mohammad Zubayer’s younger brothers, aged nine and 11, they merely cover old ground.

Rahim said he bought Burmese-language books to supplement the boys’ studies. But, after two months, he pulled his sons out of the centre. Now, they attend one of the Islamic madrassas, which have proliferated in the camps along with the new refugees’ makeshift tents. Some madrassas offer a secular education alongside religious schooling, but Rahim says the classes there are still subpar.

"Education is a right," Rahim said. "If we don’t find a way to teach our kids, what will we do?"

Obstacles to education

Money is one hurdle to providing education to more refugee children. Donors have committed only 14 percent of the $47.3 million needed to fund education in the camps, aid groups say.

A lack of space and proper facilities is also a problem. The learning centres, like most of the structures in the teeming camps, are flimsy shelters made of bamboo and plastic sheets. Of the 1,179 centres in the refugee settlements, 350 are threatened by floods or landslides in the coming monsoon season.

Then there's the fact that last year’s refugee influx was so large and so sudden that Bangladesh's government and aid groups struggled to feed and house the new arrivals, let alone provide emergency schooling.

Any wider education programme must be designed "in an organised way”, said Pawan Kucita, the UNICEF education chief in Bangladesh. “That means we have a proper curriculum, proper teachers, proper materials. Otherwise, education for the children will not be meaningful."

But the governments of both Myanmar and Bangladesh have balked at establishing a formal education system in the Rohingya camps.

There's no Rohingya-language curriculum because the language has no widely used script. Myanmar's government won't approve the Burmese-language curriculum for use in Bangladesh, said Risto Ihalainen, the coordinator for aid groups working on education in the camps. And the Bangladeshi government won't allow Rohingya refugee children to learn in Bangla, Bangladesh’s official language. That means the host country's curriculum is also off limits.

"That is the fear that the government has: If they have education in Bangla, [the Rohingya] might try to be Bangladeshi [citizens], and they will feel comfortable staying here rather than going back to Myanmar," said Nazrul Islam, education coordinator for BRAC, which runs 200 learning centres in the camps. "The textbook that we have in Bangladesh, we could use it if the government allowed us to use Bangla. As long as it is not allowed, we need to develop learning materials, which will take time."

In the absence of an official curriculum, aid groups submitted alternative education guidelines covering basic literacy and numeracy skills to the government in February. Although the authorities have not approved these guidelines, some learning centres have based their lessons around them anyway, since children are showing up.

In the hope of educating more children in the future, aid groups are developing guidelines to teach up to a Grade Eight level. But even if the government approves this, the fundamental problem of the ban on formal education remains.

"We are calling on the government of Bangladesh to recognise the right of refugee children to education," said Beatriz Ochoa, humanitarian advocacy manager for Save the Children's Rohingya response. "All education sector partners should be given the authorisation from relevant authorities to set up classrooms, organise learning activities, or, where feasible, expand temporary learning activities to ensure all refugee children can access education and develop their minds."

(TOP PHOTO:A Rohingya refugee child watches an aircraft fly overhead in Balukhali refugee camp in Bangladesh in late April 2018. CREDIT: Jason Patinkin/IRIN)

jp/il/js/ag