The 150 percent fuel price hike that sparked mass public unrest across Zimbabwe last month sent the cost of living skyrocketing: the price of bread nearly doubled in a week.

Worse is likely to come.

Combined with poor harvests, political unrest, eroded salaries, and an ongoing currency crisis, the rising costs mean the ability of many Zimbabweans to grow or afford a basic meal is under threat. More than two million people are predicted to need humanitarian food assistance this year, despite government claims to the contrary.

Crop harvests in many parts of the country have been written off due to poor rains and erratic weather patterns. Freda Mbewe, 63, is among those worst affected.

For years Mbewe grew maize in her small backyard in a working class township in Zimbabwe’s second largest city, Bulawayo. She processed it into mealie meal to make isitshwala, a traditional porridge that’s a staple for many in her community.

“I could get up to 10 20-litre buckets of maize from my field,” she said – enough to last her a few months, with some left over to sell. “There are no rains this season,” she said. “I cannot even afford the price of mealie meal.”

Shelves in some stores are running low on basic produce, while those few main supermarkets that are still fully stocked with imported staples have raised their prices to offset their increased costs.

“Old people are feeling it the most because they have no means or power to look for money,” said Jenni Williams, coordinator of Women of Zimbabwe Arise, or WOZA, a rights group that works with communities in Bulawayo.

“Food aid would be a welcome relief, but should not come at the hands of politicians,” Williams said, a thinly veiled reference to past allegations that the ruling ZANU-PF party has prioritised assistance to its supporters.

Faith-based organisations in the city are coordinating efforts to provide food assistance, especially for the elderly like Mbewe. Around the country, international aid groups, including the World Food Programme and USAID’s Office of Food for Peace, are assisting the most vulnerable.

Grain shortages

The Food and Agriculture Organisation has said 2.4 million people, about 28 percent of the rural population, will be food insecure by March 2019, largely as a result of “reduced output and low purchasing power”.

FEWS NET, a US-funded food security and malnutrition watchdog, issued a 1 February alert for Zimbabwe entitled: “Sharp macroeconomic decline expected to drive high prices and humanitarian assistance needs.”

It noted that food relief efforts targeted 234,000 people in 11 districts in December, but that “plans are in place to scale up to approximately 1.1 million people” in 30 of the country’s 59 districts during the peak of the January-March lean season.

“Poor households are accessing lower than normal agricultural labour opportunities given poor seasonal performance since October, and many are likely to harvest crops later than normal in May,” the bulletin said. “Given the increased cost to suppliers in transporting their products and milling grains, the costs of basic commodities in rural areas have increased significantly and in some cases are considered prohibitive for poor households.”

According to the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee, or ZimVac, up to 92 percent of rural households in the country rely on agriculture as their primary livelihood. Even so, farmers last year delivered just 1.2 million tonnes of maize to the Grain Marketing Board, less than two thirds of the country’s annual consumption of up to 1.9 million tonnes.

Despite this deficit, Labour and Social Welfare Minister Sekai Nzenza has insisted that Zimbabwe has enough food reserves.

Food production was also dealt a severe knock by the fuel price increase as farmers reported they were failing to access fuel for generators for their irrigation projects, leading to large scale losses as crops wilted.

Price rises

Even if there is enough grain, this doesn’t mean those who need it can afford it.

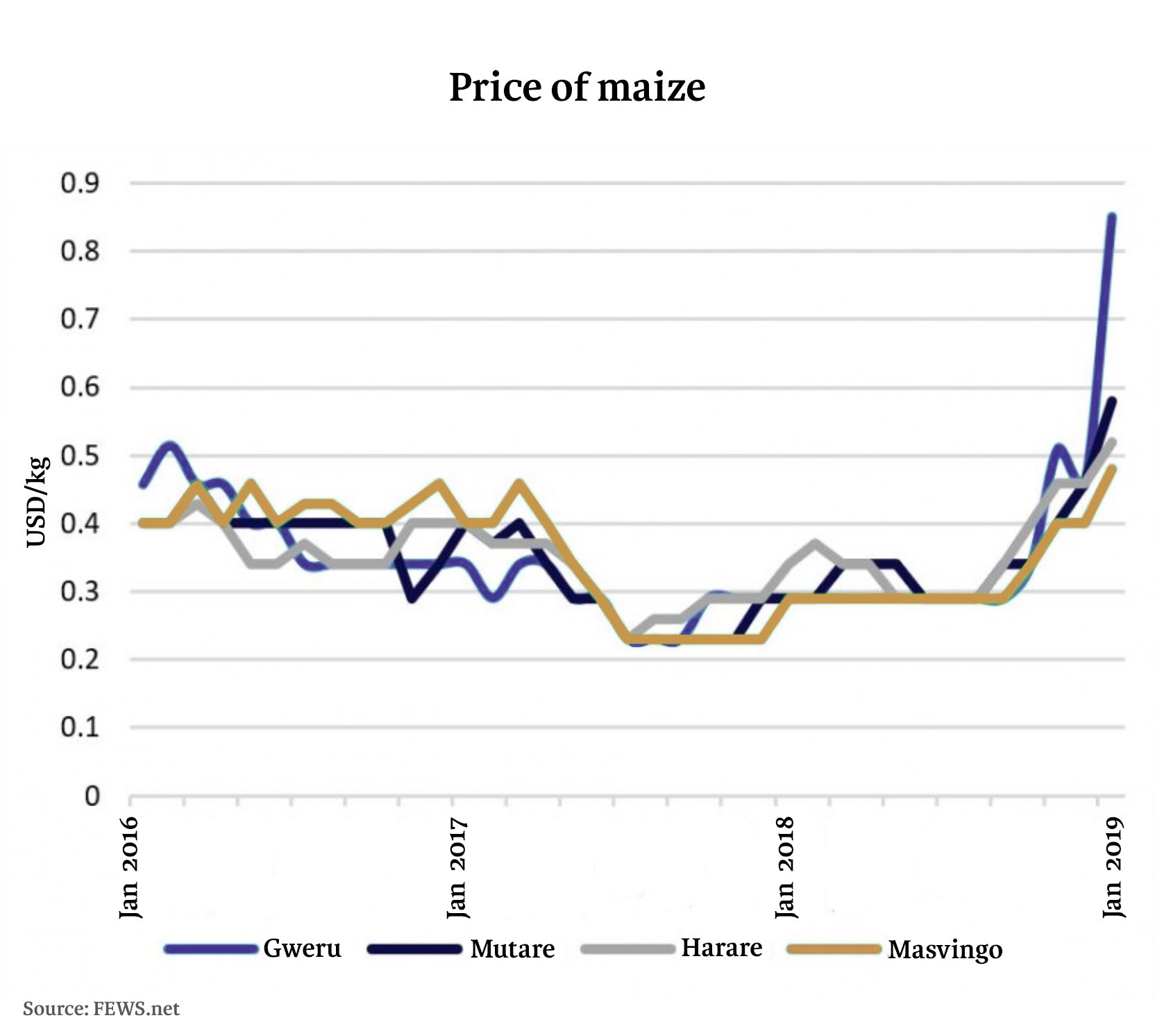

Between September 2018 and January 2019, maize grain prices increased between 50 and 200 percent, FEWS NET said, while the prices of sugar, wheat flour, and bread rose between 35 and 100 percent, and cooking oil by over 300 percent during the same period.

In stores, the cost of everything, from potatoes to toothpaste to bread, has continued to rise. A loaf that cost between 70 cents and one Zimbabwean dollar (or bond note) in December, was 1.50 at the end of January. It rose last week to between 2.00 and 2.50, before the government introduced price controls on Friday, which saw bread costs decrease to 1.90.

With domestic pantries and grain silos empty, and the cost of basic items increasing rapidly, many families have been forced to eat less. The volatile exchange rate, controlled by the illegal parallel market, has also made it virtually impossible for people to keep to a budget.

Mbewe says her 80 dollar (about US $30) monthly government pension holds no weight against the daily economic realities.

Eroded salaries, now worth less because of soaring inflation, have seen doctors, nurses, teachers, and other government employees go on strike since President Emmerson Mnangagwa claimed victory in last July’s election.

Susan Dliwayo, a primary school teacher in Bulawayo, said she can no longer afford to prepare a packed lunch for her children. Civil servants, who number close to 160,000 according to official figures, continue striking for a 300 percent salary hike to try and mitigate the rising cost of living.

“Things are terrible,” said Lazarus Mthombeni, a security guard in Bulawayo, adding that he has gone three months without a salary yet continues going to work because he has nothing else to do. “We are working but cannot afford the most basic things in life.”

Dwindling foreign reserves

With most companies importing their raw materials, demand for foreign currency has continued to rise, with the central bank struggling to allocate forex to critical industries, including food manufacturers and fuel importers.

Analysts say because Zimbabwe no longer exports as much it did, foreign currency reserves have dwindled, forcing the finance minister to introduce what he says are austerity measures that prioritise forex allocations to only a few manufacturers.

Local manufacturers complain about a lack of foreign currency to import raw materials to continue production that has already been crippled by the fuel shortages, while the Confederation of Zimbabwe Industries says the lack of forex means employers can’t pay workers in foreign currency to shield them from the escalating cost of living.

There were reports that a new currency would be introduced this week, as the government attempts to stem rising prices and cash shortages. However, Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube dismissed the claims, telling state media on Monday that currency reforms will only be implemented in the next 12 months.

Vice President Kembo Mohadi has hinted at the introduction of government price controls to make basic commodities “affordable”.

But analysts continue to warn about the unintended consequences of price controls, which previously failed and led to empty shelves as businesses struggled to stay afloat.

“In the short term, price control works in delivering cheap or affordable commodity price for key products such as mealie meal and bread. This keeps consumers happy and keep ‘food riots’ and ‘bread riots’ at bay, especially in urban areas,” said Sobona Mtisi, a UK-based Zimbabwean researcher and academic. “However, this has the unintended effect of making crops such as maize and wheat not profitable for a farmer to grow as they do not deliver an economic profit.”

With poor rainfall predicted and an increased need to help farmers during the 2019/2020 season, the UN is stepping up its support.

“FAO is assisting drought affected smallholder farmers to access subsidised drought tolerant seed varieties to restore their productive capacity,” Alain Obin, an agency representative in Zimbabwe, told IRN via email.

Further trouble ahead

In a newspaper article last month, University of Zimbabwe economist Professor Tony Hawkins wrote that “few [people] take seriously the budget forecasts of 3.1 percent growth and 22.3 percent inflation in 2019” – figures from the largely discredited national statistics agency.

Because the bulk of the country’s agro-economy is dependent on rainfall, he said lower levels over the next three months (among other factors) mean “growth will fall short of target and could turn negative”.

With continued suppressed production, and the bulk of the goods sourced outside of Zimbabwe, the rising price of basic commodities is expected to further stoke inflation.

“At best, inflation is likely to average 40 percent,” Hawkins wrote. An uptick in inflation has in the past led to shortages of basic commodities as manufacturers struggle to keep pace with rising production costs. It has also led to panic buying as consumers stock up to try to beat ever-changing prices.

Zimbabweans with ready funds are now shopping in neighbouring Botswana and South Africa, where prices are considered cheap. But this means increased travel costs and the inconvenience of long two-way journeys.

The crisis has spurred a new wave of migration across the border, as an increasing number of Zimbabweans seek to make a living elsewhere.

South Africa’s main opposition party, the Democratic Alliance, raised fears last month that the crisis in Zimbabwe could turn into a humanitarian nightmare, noting that the number of Zimbabweans entering South Africa at the height of last month’s unrest spiked to more than 130,000 in a single day.

South Africa has so far stuck to its policy of “quiet diplomacy” in dealing with Zimbabwe’s drawn-out crisis, but Nathan Hayes, a country analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit, warned that a new surge of migrants across the border “could spark intervention”.

(TOP PHOTO: Crop harvests in many parts of the country have been written off due to poor rains and erratic weather patterns. CREDIT: Marko Phiri/IRIN)

mp/si/ag