The Catholic Church in the Democratic Republic of Congo is now a powerful voice of opposition to President Joseph Kabila’s continued unconstitutional stay in power, but the Church’s spiritual authority is yet to translate into political muscle.

In December and January, along with a so-called secular coordination committee, the Church organised two separate protest events in the capital, Kinshasa. They were violently broken up by police using live rounds and tear gas, and at least 15 people were killed.

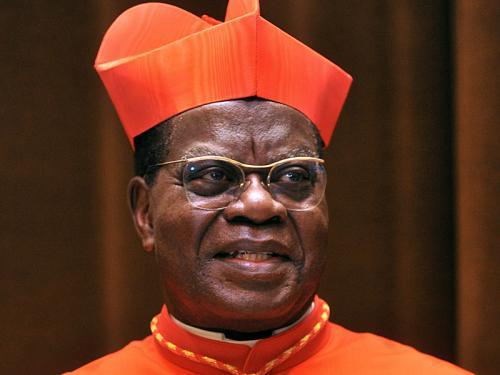

But while protesters’ placards demanded “Kabila dégage” (Kabila out), some demonstrators also sang “Kabila, you are no longer our president, our new leader is Monsengwo” – a reference to Cardinal Laurent Monsengwo Pasinya, the Catholic archbishop of Kinshasa.

Monsengwo, 79, is the de facto head of the Catholic Church in the DRC, one of the few effective nationwide institutions in the country, with 32 million followers out of a Congolese population of 80 million.

In condemning the brutality of the police in suppressing the protests, Monsengwo drew a distinct line between a government many regard as illegitimate, and Congo’s long-oppressed citizenry.

"It's time that truth won out over systematic lies, that mediocre figures stand down, and that peace and justice reign," the cardinal said, the sort of stand that has helped win him support beyond his Catholic congregation.

Troublesome priest

The comparison has been made between Monsengwo, and Étienne Tshisekedi, a veteran opposition leader who commanded a mass following before his death last year in Belgium.

“We were like orphans because we haven’t had anyone to speak for us since he passed away,” said protester Edith Ekofo. “Now, God has sent us somebody who will liberate us from the slavery and dictatorship of Kabila and his yes-men.”

Kabila has been in power since 2001, taking over from his father, a former rebel leader, when he was assassinated. Kabila was supposed to step down after his second and final constitutional term came to an end in 2016, but instead clung on.

The Catholic Church negotiated a deal – known as the Saint Sylvester agreement – enabling Kabila to stay in power to organise elections in 2017. But the poll has now been pushed back to December 2018 – a date many Congolese fear will again be ignored.

The Church has played a key mediation role in DRC’s complex history. It has proved to be a “potent actor – but also a prudent one”, said Hans Hoebeke, a senior analyst with International Crisis Group.

Its 160 parishes in Kinshasa alone serve as a grassroots “barometer for social and political tension [which can] create a considerable level of pressure” on the clergy, he added.

Kabila’s reneging on the Saint Sylvester agreement clearly angered the Church. “Somehow, they feel betrayed and humiliated by Kabila’s refusal to implement even one iota of it as agreed by all parties,” said political analyst Jean-Marie Kabamba.

“By now they are truly convinced that this man is not to be trusted,” he told IRIN. “Besides, Kabila is surrounded by former dignitaries of the Mobutu regime [prior to Kabila’s father] who only have one thing on their mind – to stay in power as long as they can.”

Third-term fears

Kabila’s Mobutu-inspired strategy seems to be working. He has not ruled out seeking a third term, and there is widespread concern he may call a referendum to change the constitution to allow him to do just that.

Kabila also has, so far, the loyalty of the security forces. In the December and January protests, the police showed no compunction in lobbing tear gas into churches, beating and robbing parishioners, and detaining priests.

In the troubled east and southeast of the country, where rebellion has long simmered, the UN peacekeeping mission known as MONUSCO has reported a surge in extrajudicial executions by “state agents”.

According to MONUSCO’s annual human rights report, there were 1,176 recorded summary killings in 2017 – a two thirds increase on 2015.

Monsengwo, a long-standing human rights campaigner, has not shirked from condemning what he describes as the “so-called security forces” for their excesses.

“There is no greatness in the use of weapons to kill people,” he lectured. “’Let’s take care, my brothers and sisters, because whoever kills by the sword will perish by the sword.”

It is that kind of language that has put the Church on a potential collision course with the authorities.

Government spokesman Lambert Mende Omalanga has slammed Monsengwo for “insulting” the country’s leaders and the security forces – legally a punishable offence.

Kabila also weighed in during a press conference on 26 January, his first in five years. "I don’t have my Bible right here with me... but nowhere in the Bible is it written that Jesus Christ presided over an electoral commission,” he said.

“To Caesar what belongs to Caesar and to God what belongs to God,” he warned. “We must not mix the two [religion and politics], because the results will be negative.”

Weak opposition

Kabila failed to allay concerns he will seek to remain in power beyond 2018, and instead complained that the cost of an election would be “exorbitant”. He also demonstrated no sympathy over the deaths of the protesters in January, even suggesting a new law was needed to “reframe” the legality around such demonstrations.

The long-discredited political opposition seems powerless to derail any bid by Kabila to extend his stay in power.

“As long as the regime has the army, the justice system, the intelligence services, and the police that it can use to put them behind bars, and money to poach them, the opposition will remain paralysed and divided, and therefore useless,” said Kabamba.

ICG’s Hoebeke agreed. “The opposition is a problem. Its leadership lacks courage and vision, and it counts on others [the international community, the street, public opinion] to do the work for them… The entire political class lacks popular legitimacy.”

More than 120 armed groups operate in the east and southeast of the country, a long way from Kinshasa. Their organising principles seems to revolve around the killing of civilians, sexual violence, and plundering resources. Absent of a political agenda, their activities have generated one of the world’s worst humanitarian crises.

“Despite some attempts at regrouping, armed groups remain mostly fragmented,” said Hoebeke. “[But] it is not to be excluded that the longer this situation lasts a more consolidated group will appear… or that the security forces will be either further weakened or totally overstretched.”

Defiant government

The government has been largely defiant of the international community and hostile towards MONUSCO, which has repeatedly called on Kinshasa to respect human rights.

“Further delays in the electoral process not only risk fuelling political tensions but also compounding an already fragile security situation,” peacekeeping chief Jean-Pierre Lacroix told the UN Security Council earlier this month.

Kabila, who has ignored calls by UN Secretary-General António Guterres to investigate the killings of protesters, fired back. “We have to clarify our relations with MONUSCO in the coming days,” he said at the press conference, without elaborating.

“This is not a government that is serious about delivering free and fair elections in an open and peaceful, safe environment in which all parties can express themselves without fear of sanction,” said Stephanie Wolters, head of the peace and security research programme at the Institute for Security Studies.

“This electoral crisis is a key driver of growing instability in the DRC,” she told IRIN.

The country is effectively in political stalemate, noted Hoebeke.

“The regime wants to hold on to power, but does not have the legitimacy or the strength to push this through,” he said. “There is, however, no other source of power that has the strength, legitimacy, and determination to force the regime out.”

Isds/oa/ag

TOP PHOTO: Protests in Kinshasa 19/20 December 2016