“I am planning to work with all Burundians [to bring about] a better politics that brings everybody on board, so that we have a better country,” he told the Swahili service of Voice of America, putting paid to rumours that he might have been assassinated. His location was not disclosed.

Radjabu’s 1 March jailbreak, which was well organised with outside assistance, adds to the uncertainty and tension pervading Burundi in the run-up to a presidential election, scheduled for June. The most pressing question related to this poll is whether President Pierre Nkurunziza, a comrade-turned-nemesis of Radjabu’s, will run for a third term despite a constitutional limit of two mandates.

IRIN examines the key issues.

Who is Radjabu?

An agronomist by training, Radjabu served in both the military and political wings of the National Council for the Defence of Democracy-Forces for the Defence of Democracy (CNDD-FDD) rebel group during Burundi’s 1993 to 2005 civil war. After the organisation became the ruling political party under Nkurunziza in 2005, Radjabu served as its secretary-general until he was sacked and then convicted of fomenting an insurgency in 2007.

Although he never held government office, he was widely seen as the most powerful and effective member of the party, whose intelligence arm he once controlled. As such he would have directed a 2006 crackdown that saw many opposition politicians arrested.

During his incarceration he continued to enjoy support from senior members of the CNDD-FDD.

Why was he jailed?

Radjabu’s conviction in April 2007 on charges of insulting the head of state and threatening national security by encouraging an insurrection – which earned him a 13-year jail term - has been widely attributed to the challenge he posed to Nkurunziza. Many in the party felt it was Radjabu, rather than the president, who did much of the administrative heavy-lifting of governing the country.

While behind bars, he was frequently described as Burundi’s “most famous political prisoner”.

In December, rumours of his imminent release prompted jubilant crowds to gather outside Bujumbura’s high security Mpimba prison. Rather than being freed, Radjabu was put in solitary confinement and placed under near-constant watch.

How did he get out?

By his own account, with the help of accomplices both inside and outside the prison, who liberated not only Radjabu but also his co-accused, his bodyguard and his steward. So smooth and silent was the nighttime operation, according to one account, that nobody in the jail knew of it until well into the next day.

Police spokesman Liboire Bakundukize said Radjabu “was helped by at least three guards, including the chief warden in charge of the prison's security.”

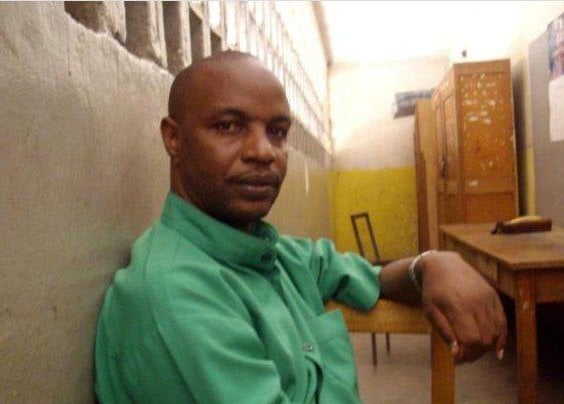

A few days later, a photo appeared online of Radjabu, posing next to his co-accused, Ndindi Ribakare and erstwhile Nkurunziza right-hand-man Col Manasse Nzobonimpa, who had arrested Radjabu in 2007 on the president’s orders. The location and date of the photo could not be verified.

One of the website’s readers commented, “We are very happy to see that you are out of prison and we have much hope in you. Those protected by God cannot be harmed.”

Why does this matter?

Because this is an election year in country with a long history of settling power struggles by force of arms, with devastating effects. (Some 300,000 people were killed in the civil war). Politically motivated killings are regularly reported and over the New Year the army battled an unidentified armed group for five days. Despite post-war disarmament operations, many weapons remain in private hands in Burundi.

A resumption of the civil war is not deemed likely, at least not along the Hutu-Tutsi lines of the previous conflict. But there is widespread discontent with the lack of any tangible peace dividend or economic growth and the extraordinary wealth of a small well-connected elite from both ethnic groups.

Now the upper echelons of the government and security apparatus are divided over whether Nkurunziza should run again. The president himself has not declared his intentions, but his supporters dismiss the constitutional bar as irrelevant, pointing out that his first mandate followed a parliamentary appointment, not a national election. The president recently relieved one man reportedly in the don’t-run camp, Godefroid Niyombare, of his duties as intelligence chief.

As a fugitive from justice, Radjabu himself cannot run in the election, but his continuing popularity and influence within the ruling party could make it impossible for Nkurunziza to do so.

“Many powerful people who worked with Nkurunziza don’t want him stand again,” Gilbert Bucyeyeneza, a Burundian journalist working with Iwacu Newspaper told IRIN.

“There could be violence during elections if he tried to force it” he added.

Pierre-Claver Mbonimpa, Burundi’s best known human rights activist, said those in the ruling party opposed to a third presidential term might now team up with Radjabu.

Mbomimpa has frequently spoken out against abuses allegedly committed by the ruling party’s youth wing, the Imbonerakure.

“There is worry that the government might want to use Imbonerakure, something likely to spark violence,” he said.

Radjabu himself did not directly address the issue of a third term, but his reference to a “new politics” left little doubt as to his position on the matter.

is/am/rh