What is happening in Yemen looks like “famine” as it is commonly understood – children, for instance, are dying of starvation. Yet the difficulty of collecting data means that an official famine, which has a technical definition and a high threshold, may still not be declared.

Even before the battle for Yemen’s Red Sea port city of Hodeidah intensified in the past week, threatening to cut off one of the country’s key lifelines, millions of Yemenis did not have enough to eat.

Last month, the UN’s humanitarian chief Mark Lowcock delivered the latest in a series of dire warnings about the food situation in Yemen – a country that has been at war for more than three and a half years and heavily reliant on food imports for decades. The number of people facing “pre-famine” conditions, Lowcock said, had reached 14 million – half the country. That meant there was “a clear and present danger of an imminent and great big famine.”

As the fight for Hodeidah puts an increasing number of civilians in the line of fire, the UN may have a strategic interest in making such strong statements. Declarations of famine, or even the threat of them, often lead to greater leverage, increased funding, and more media attention.

But the UN cannot declare a famine simply because large numbers of people are going hungry, or even dying. It adheres to the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) system – a method of analysing food insecurity designed to pull the process of declaring famine away from politics by using uniform measures that can be reliably compared across countries.

This is fine in principle, but in practice can be problematic.

“Data collection in Yemen has been horribly difficult since the start of the conflict,” said Michael Neuman, director of studies at MSF-Crash, an affiliate of the medical charity that conducts analysis of MSF’s work.

“By the time we get to famine, a response is almost already too late.”

The last time famine was declared was in South Sudan in 2017, in two counties. By the time the UN made it official, it is estimated most of the hunger-related deaths had already happened, and many more died in areas where there was never, technically, a famine.

As Peter Thomas, an analyst at Famine Early Warning System Network (FEWS NET), a US-funded food security monitor, put it: “By the time we get to famine, a response is almost already too late.”

Crossing a threshold in the IPC system and making a declaration may make no immediate difference on the ground, where children still die and parents mourn, but it can have longer-term ramifications. One Security Council diplomat, who asked to remain anonymous, told IRIN that it would at least push diplomats, who this year passed a Security Council resolution on food security and conflict, to further action. The resolution raises the possibility of sanctions against “individuals or entities” who obstruct the delivery of, access to, or distribution of humanitarian assistance.

A famine declaration would likely be a major PR hit for the government of internationally recognised President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi and the Saudi Arabia-led coalition that backs it. Despite their own interference in relief efforts, for the Houthi rebels, it could be an image win, as they have long argued that the coalition and its allies are to blame for the humanitarian crisis.

A declaration would be especially politically charged given the international spotlight on Saudi Arabia – and its US and UK ties – since the killing last month of dissident Saudi journalist Jamal Khasshogi in its Istanbul consulate.

Is famine likely to be declared?

Lowcock told the Security Council that a current round of food security assessments would conclude in November, warning that it could result in an official declaration of famine in at least some parts of Yemen.

José López, IPC global programme manager at the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organization, confirmed to IRIN that analysis was taking place in northern and southern districts. He said final results were expected by the middle of the month. “However, this schedule is subject to change given the evolving situation in Yemen,” he cautioned.

The IPC has five “phases” of food insecurity, and for a country to reach the “catastrophic” phase 5 – famine – the following criteria must be met: at least 20 percent of households face extreme food shortages; more than 30 percent of children younger than five suffer from acute malnutrition (measured by weight and height); and at least two out of every 10,000 people are dying every day.

Reliable data has proven notoriously difficult to obtain in Yemen, where war has split the country between Houthi rebel-controlled regions and areas dominated by the UAE and Saudi Arabia-backed government of Hadi and their allies.

Once data is compiled, a technical working group made up of staff of the UN, NGOs working in the country, and government agencies should arrive at findings through consensus. If the group suspects famine at the end of that process, a team of experts appointed by the IPC is brought in to further consider the data. Finally, any declaration is made either by the UN, the national government, or both. This process, however, is still evolving, and a new IPC manual – as yet unpublished – is being tried out for the first time in Yemen.

In recent conversations with more than half a dozen aid workers and food security experts, some, including technical staff with access to UN figures on hunger in Yemen, said they believed the threshold for famine had already been crossed in certain parts of the country.

Others were less sure and said famine “could” be present, or predicted that it would not be declared at all – possibly because the required data remains unavailable. In a grim irony, famine may prove impossible to declare because humanitarians are unable to count the dead in pockets of the country from that very famine.

So what now?

Last year’s annual assessment on hunger in Yemen found that at least two of the thresholds for phase 5 “were either already exceeded or dangerously close” in about a third of Yemen’s 333 districts, according to Lowcock.

But the final indicator, the death rate, was particularly difficult to ascertain.

An ideal data collection process would include collating the results of multiple surveys: aid or health workers going door to door filling out surveys that ask questions about deaths in the family and what the family ate recently, for example. It could also collect a range of data from public hospitals and clinics. This is not available in all parts of Yemen, however.

As international agencies have limited freedom of movement, much of the data for the IPC process has been gathered by Yemeni civil servants conducting UN-funded surveys, a source familiar with the current IPC process told IRIN. A Ministry of Health official, for example, will run families through a structured questionnaire. In Yemen, these surveys on food availability and nutrition make up the bulk of the data under consideration. Gathering reliable mortality information can be particularly hard, the source added, as it runs into both political and cultural sensitivities.

“The IPC is hugely important, but like any methodology its applicability depends on conditions on the ground,” said the UN’s head in Yemen, Lise Grande. “Given the complete breakdown in the health system, and the total inability to realistically collect mortality figures, we will almost certainly never know concretely what is going on with the mortality indicator.”

An aid expert who asked to remain anonymous because they were not authorised to speak to the media while assessments in Yemen were ongoing said it seemed the IPC system “is designed not for conflict settings, in the sense that – as per Lowcock's statement – it's very hard to get the data if there are a lot of locations that are inaccessible.”

Some aid groups, including Médecins Sans Frontières, have been sceptical of the most alarming warnings coming from Lowcock and others, cautioning against getting too far ahead of hard figures. “There is no quality data available to declare that a famine is imminent,” MSF said in response. The group said its centres in five regions did not indicate the likelihood of famine. However, it also said NGOs and UN agencies were unable to mount the kind of broad surveys that would provide the true picture. Access restrictions were “political and administrative” as well as security-related, it said.

“What we are relatively comfortable in stating right now is a general state of famine in Yemen is not what’s happening,” Neuman of MSF-Crash said. “This is not underestimating the difficulties that Yemenis are going through.”

Do declarations come too late?

The lack of data doesn’t make the suffering less immense, as past famines and near-famines have shown.

“Even in phase 4, before reaching phase 5, there is an association with high levels of increased malnutrition,” said Thomas of FEWS NET, which uses the same methodology as the IPC but conducts its own research.

“A million people could die without a famine being declared.”

The fact is that the data often follows the deaths. Thomas pointed out that in Somalia, where famine struck in 2011, more than half the starvation-related deaths were adjudged to have occured prior to the UN’s phase 5 declaration.

The same happened in South Sudan. By the time two counties were briefly under IPC phase 5 there in 2017, most of the deaths had already happened. A small portion – 1,500 or so – of those who ultimately perished from starvation-related causes died in those two counties during the period, said Alex de Waal, executive director of the World Peace Foundation at Tufts University, and author of several books on famine.

“It may be that we are going to have a non-famine declaration [in Yemen], but an indication that hundreds of thousands may have died,” de Waal said. “A million people could die without a [phase] 5 famine being declared.”

An alert from FEWS NET late last month listed trigger after trigger – fighting near the port of Hodeidah, ongoing currency depreciation or trade disruptions – that could hurl large segments of Yemen’s population into phase 5. “Although high quality data on current outcomes is limited, awaiting improvements in data availability and quality may only confirm the severity of outcomes after they occur,” it warned.

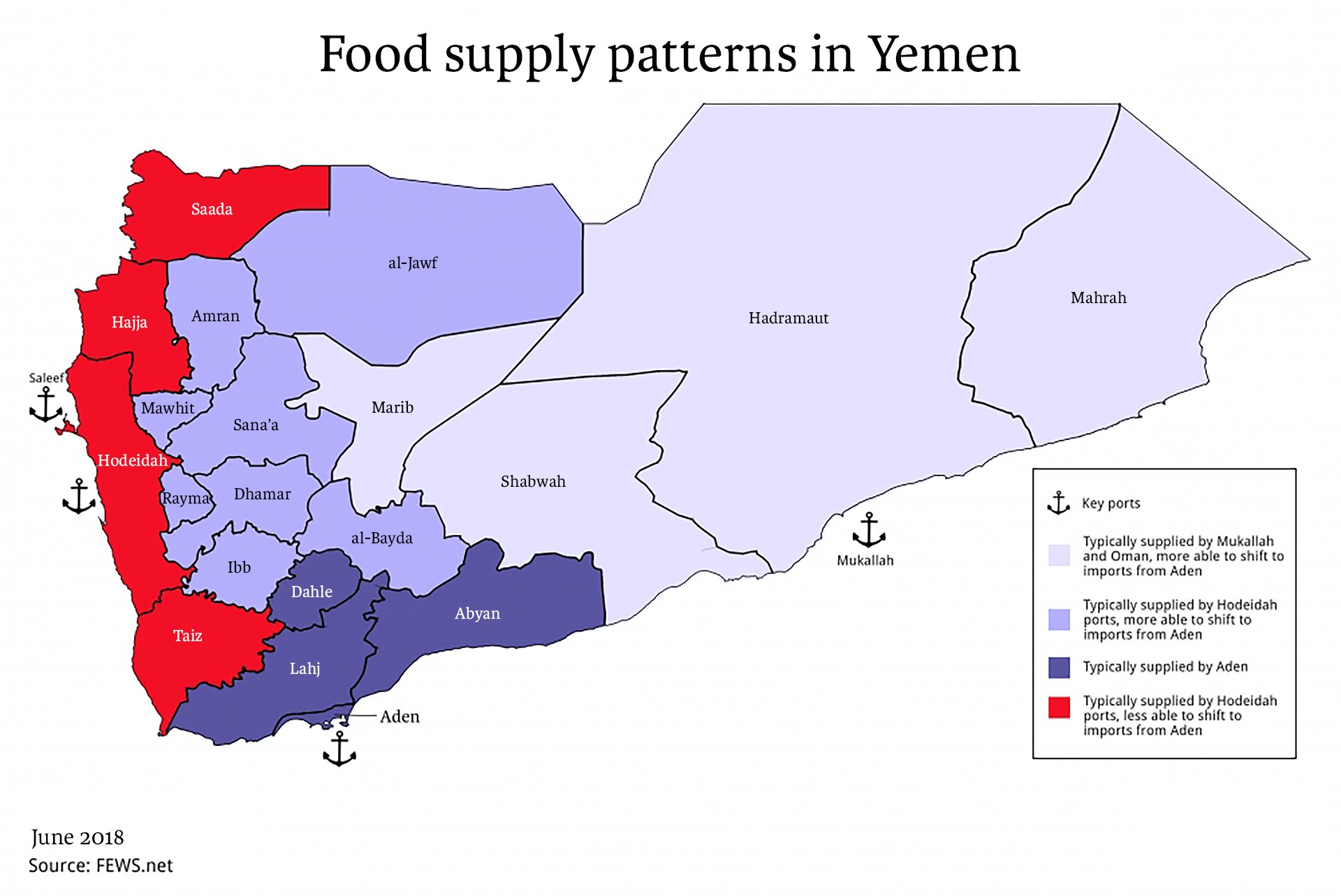

The monitoring group said that if imports through Hodeidah and a nearby port were to halt, the places most likely to fall into famine first were those that depend heavily on their trade, have ongoing conflict, and a large number of displaced people. These include the provinces of Hodeidah, Taiz, Sana’a, Hajjah, and Saada.

Political interference?

The IPC structure was developed in part because field analysts looking at hunger in Somalia were receiving pressure, including death threats, intended to impact their analysis. After the data is collected, it ultimately relies on a consensus process involving numerous actors, leaving it potentially vulnerable to influence.

Political considerations are especially pressing in Yemen, as the UN hopes peace talks – already delayed – will start at the end of the year and the groups fighting on the ground are keen to use the humanitarian situation to bolster their positions.

“Different stakeholders have different reasons that they want it to be declared or not declared,” said Christopher Mzembe, head of programmes for the Norwegian Refugee Council in Sana’a.

It is rare for a government – in this case Hadi’s administration and the coalition it works with – to want a famine declared on its watch. This may be doubly true given that the coalition has been accused of delaying vital imports, especially after it temporarily closed all Yemen’s borders after a Houthi rocket attack. The Emiratis and Saudis, along with other coalition members like Kuwait and their US and British backers, have provided the majority of the funding for the UN’s 2018 response plan for Yemen – money that would have failed to avert famine.

The Houthis have also been accused of extorting incoming ships for money and diverting aid to their own people, but despite this fact a declaration of famine may still play into the rebels’ hands.

“In the northern [Houthi-controlled] governorates, the local authorities are very keen for [famine] to be declared because they want to show how bad the coalition is,” explained Mzembe. “On the other side you have this big UN structure and other donors who have put a lot of resources in Yemen, and they would like also to demonstrate that the resources are making a difference, so they would be more cautious in terms of admitting the extent to which famine might be present right now.”

There is precedent for government interference. According to several food security experts IRIN spoke with, the government of South Sudan has actively interfered with assessments in that country. The question of what role a government – in Yemen’s case, there are two – would play in officially declaring famine in Yemen remains unclear. According to the last published IPC manual, the technical working group should be chaired by a government representative.

So while new November assessments should come in soon – and fighting continues to escalate in Hodeidah and other parts of Yemen – aid agencies, warring parties, and the UN bodies may not come to a consensus agreement on famine any time soon.

The IPC system may not be perfect for conflict situations like Yemen, but there is no real alternative. “The politics around declaring phase 5 are deeply problematic, but it is still useful,” argued de Waal, describing the system as “the best we have for now”.

(TOP PHOTO: A doctor measures the arm of Ali Mohammed Ahmed Jamal, 12, as he is treated for malnutrition at a hospital in Sana'a, Yemen, on 2 November 2018. CREDIT: Mohammed Huwais/UNICEF)

so/bp/as/ag