Outside the mosque, the UN peacekeepers were ready and waiting when the war came to Bangassou, a mid-size town deep in the Central African Republic countryside. For the Muslim community – under attack from a “self-defence” Christian militia – the men in blue helmets were the only ones they trusted to keep them safe.

At first light, hundreds of men, women, and children left their homes and rushed towards the peacekeepers, who sat in armoured vehicles stained orange by dust and dirt. Bullets fizzed through the air as the militiamen, armed with hunting rifles and machetes, picked off the weakest on the streets. It was a perilous journey, but it was worth the risk.

Or so they thought.

For a while the peacekeepers – from a Moroccan battalion – stood their ground and fought back as the community took shelter inside the mosque. But at roughly 6am, with one of their men bleeding to death and no reinforcements arriving, the peacekeepers switched on their engines and returned to their base.

For the next three days, Bangassou’s entire Muslim community was trapped in the mosque, left to fend for itself. When a unit of UN troops from Portugal finally arrived to escort them to the grounds of a local Catholic church, around 30 people had lost their lives.

A grainy video of the siege, shot from inside the mosque by a Bangassou resident and shared with IRIN, captures the horror with alarming detail. In a dark prayer hall, hundreds of frightened women and children huddled together, chanting “Ya Allah” (“Oh Allah”), over and over.

In a makeshift infirmary, young men sprawled on the floor with bullet wounds and bone fractures. Outside a madrassa that had become a morgue, a corpse slumped face down in the red dirt, lower legs poking out from a shroud.

“Where is the international community?” the man who filmed it, 35-year-old Salethem Djanaladihe, can be heard saying in the background.

Almost a year later, that question that still occupies Djanaladihe every day. During the siege, he lost two brothers, who were killed defending their homes, and his father, who was shot next to a water pump 50 metres from the mosque.

Now, in his spare time, he sits in the camp in the church grounds, hunched over a tatty old laptop, watching and re-watching the video. Using images and witness testimony, he is slowly building a legal case against the militiamen and the UN peacekeepers who were supposed to stop them.

One day, he said, he will use it as evidence in trial – and he is setting an ambitious target.

“I will keep it for the International Criminal Court,” he said.

- Peacekeepers face situations where there is often no peace to keep, and they work with a mind-set, training, and equipment that many say is stuck in the past

- Dragging scandals over sexual abuse and civilian killings have tarnished peacekeepers’ credibility

- 2017 was the deadliest year yet: 13 peacekeepers killed

- The UN peacekeeping mission began in 2014 after civilian massacres and ethnic cleansing carried out by Christian and Muslim militias made international headlines

- Violence erupted again in 2017, with little media attention

- One in four Central Africans is now displaced and half the population needs humanitarian assistance

- Previously peaceful southeastern towns like Bangassou are now at the centre of conflict

- The UN peacekeeping mission is under-resourced for the scale of the challenge, with 13,000 troops in a country one-and-a-half times the size of France

Old-style peacekeeping for new-style conflict

The attack on Bangassou’s Muslim community last May marked one of bloodiest episodes in a new phase of conflict that has convulsed the Central African Republic, a landlocked former French colony of 4.7 million people.

It also marked a low point for the UN’s peacekeeping mission in CAR, known by its French acronym MINUSCA. Its primary objective is to protect civilians, but its troops have repeatedly come up short.

They are deployed in an environment far removed from peacekeeping missions of the past, when lightly armed men stood between warring factions in the aftermath of armed violence. They were governed by the so-called “holy trinity” of peacekeeping: impartiality, host state consent, and minimum use of force.

Now, in CAR and elsewhere, blue helmets find themselves in situations where there is often no peace to keep, working with a mind-set, training, and equipment that many say is stuck in the past. Bangassou is just one example.

The MINUSCA mission began operating in CAR in September 2014, with a mandate to help restore order in a country torn apart by civil war. The year before, a mainly Muslim rebel alliance called the Séléka had ousted then-president François Bozizé after killing and pillaging its way through the sparsely populated countryside. In response, a mainly Christian self-defence militia, called the anti-balaka, rose up, killing Muslim civilians in what human rights groups deemed ethnic cleansing.

Largely peaceful elections in 2015 failed to bring durable peace, and in 2017 the bloodshed started again. Every few days brought fresh news of violence against civilians in far-flung corners of the country. Each episode chipped away at the credibility of a peacekeeping mission that was supposed to make sure such things didn’t happen.

While MINUSCA has been rightly credited for saving countless lives, the peacekeepers have found that their job of protecting civilians rubs up against the reality of operating in a country one and a half times the size of France, with a government that barely exists outside the gates of the capital, Bangui.

And a series of scandals, including widespread sexual abuse of local women and girls by peacekeepers and the killing of civilians, has profoundly damaged trust among the population the peacekeepers are supposed to serve.

This year, one in four Central Africans is either internally displaced or living as a refugee in neighbouring countries. Half the population is in need of humanitarian assistance.

“The level of violence and displacement is unprecedented over the course of the past five years of conflict,” said Evan Cinq-Mars, UN advocate at the Center for Civilians in Conflict, a Washington-based NGO.

“Most of them were our friends before”

Bangassou is at the epicentre of the current violence. It’s a sleepy town on the border with the Democratic Republic of Congo, roughly 700 kilometres from Bangui. It has a central market of small kiosks and a large red-brick, Roman Catholic church built in the 1960s. Its roads are uneven and unpaved. Plumes of red dust rise at the wheels of the few vehicles that use them.

Until last year, the town was widely seen as a model of social cohesion. It had managed to escape the worst of the conflict that swept through CAR in 2013 and 2014. Now, its Muslim community lives packed into the grounds of a Catholic seminary, unable to walk more than a few metres without risking death.

“See that tree over there,” said camp coordinator Ali Idriss, pointing towards the edge of the camp. “Get too close and the militia will shoot you.”

Conflict spread to Bangassou and the southeast through a complex set of dynamics. First came a split between two of the largest factions that made up the Séléka: the Popular Front for the Renaissance of the Central African Republic (FPRC) and the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (UPC), made up of fighters from the country’s historically nomadic Fulani community.

In late 2016 the two groups began fighting for control over CAR’s rich natural resources. Seeking to take over UPC-controlled mining sites, the FPRC teamed up with a faction of the anti-balaka, stirring up deep-rooted anti-Fulani sentiment among local populations to aid their cause.

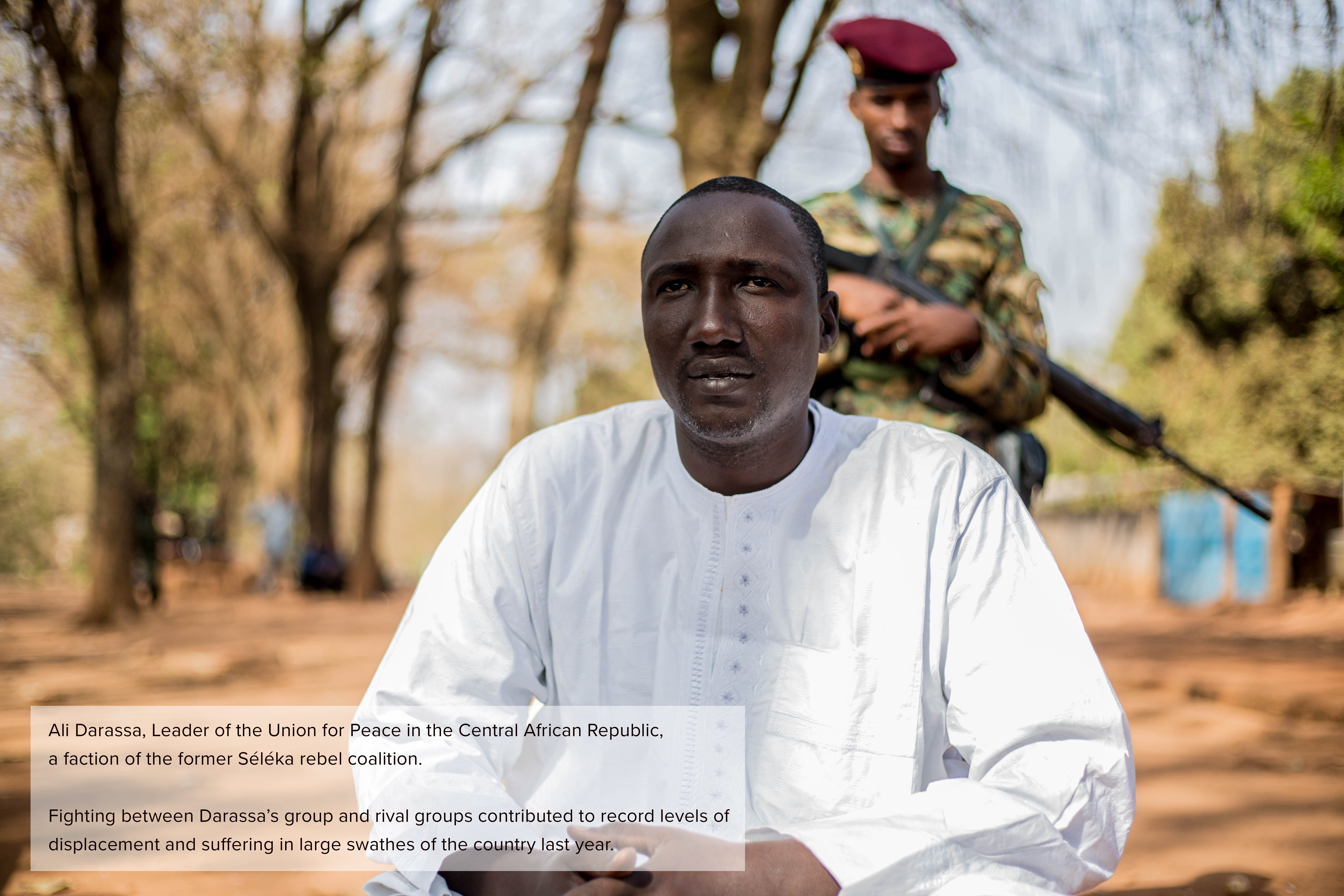

The situation deteriorated after a decision by the UN to dislodge UPC leader Ali Darassa from his stronghold in Bambari in February 2017. The aim was to prevent open fighting in the second largest town in CAR, where FPRC troops were advancing towards.

But the decision simply displaced the problem south as Darassa searched for a new home. Local populations, already frustrated at the increasing presence of UPC fighters since 2016, grew increasingly radicalised. Wherever Darassa moved, self-defence groups followed. So did the violence.

To make matters worse, American and Ugandan troops deployed in the southeast on an African Union operation to hunt down Joseph Kony’s infamous Lord’s Resistance Army ended their mission, creating a security vacuum in an area the size of Tunisia.

Bangassou’s fortunes began to change early last year as fighters from an ex-Séléka faction, the Union for Peace in the Central African Republic (UPC), gathered in the southeast.

Simultaneously, American and Ugandan troops taking part in an African Union operation to hunt down Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army, a guerrilla group, ended their mission.

Young men from Christian and animist communities mobilised into militias that stepped into the security vacuum. A new generation of armed groups disguised as “self-defence” were born.

They began by slaughtering civilians in Bakouma, a small mineral-rich town around 50 kilometres from Bangassou. Then they moved to Bangassou itself, where they justified their presence by spreading false rumours of an imminent assault by the UPC. An unknown number of locals in Bangassou joined them.

“Most of them were our friends before,” said Zanaba Hamat, a 47-year-old Muslim whose elderly father was shot dead by the militia inside his home. “Suddenly, they changed and wanted to kill us.”

Warning signs

Many say MINUSCA could have done more to stop the violence, noting missed warning signs and poor performance elsewhere in the country. Starting in January 2017, the mission received reports of youths being inducted into militias. Local media was broadcasting programs filled with violent hate speech. There were “no lack of warnings that the conflict was moving from the centre of the country down to the southeast,” said Cinq-Mars, pointing to the increased presence of UPC in the region and the withdrawal of the Americans and Ugandans.

Questions have also been raised about the performance of the Moroccan contingent in other areas. As well as leaving the mosque in Bangassou, a report by AFP claimed that its peacekeepers failed to act in nearby Gambo, where clashes between self-defence militia and UPC fighters last August left dozens of civilians dead, including six Red Cross volunteers.

Last November, the head of UN peacekeeping, Jean-Pierre Lacroix, announced an independent inquiry into the mission’s performance in the region. It was led by a retired general, Fernand Amoussou, and focused on Bangassou, Gambo, and Bria, a diamond-mining town further north.

When the report was published in January, however, a brief press release was the only thing made public. A well-placed source told IRIN the full report was circulated to a few officials and watermarked with individual names to discourage leaking. This was seemingly to avoid publicly embarrassing the troop contributing-country whose peacekeepers were responsible for the towns where all three incidents occurred: Morocco.

“The report is being held exceptionally closely,” said the source. “An executive summary will likely never be released.”

Forecasting and responding to inter-communal violence isn’t easy – something MINUSCA’s 58-year-old Gabonese chief, Parfait Onanga-Anyanga, was at pains to point out during a nearly two-hour interview in Bangui.

While the movement of uniformed ex-Séléka combatants can be easy to track, he said, in Bangassou columns of vehicles or groups of fighters did not enter the town before the clash. The combatants were groups of young men in street clothes who arrived on motorbikes that they rode over the dozens of bush paths that criss-cross the region. When they arrived, large numbers of men born and raised in the town joined them.

“Nobody was expecting communities that had been living together to do what they did,” said Onanga-Anyanga. “The violence was coming from within society, and we were taken off guard.”

A large, impenetrable country

Before the violence erupted in Bangassou, the peacekeeping mission was working to control violence in dozens of other hotspots across CAR. The geographic scope of these attacks, in a country Onanga-Anyanga pointed out is the size of Afghanistan, left the mission’s 13,000 troops more stretched than ever before.

“At the height of the conflict in Afghanistan, the international community had mobilised up to 150,000 troops,” he said. “What do we have here?”

The lack of troops meant that by the time fighting broke out in Bangassou, the small Moroccan battalion was the only group of peacekeepers available. With a MINUSCA base under attack by the militia at the same time as the mosque, Onanga-Anyanga said the peacekeeping force had to protect the camp’s perimeter. Had the two armoured personnel carriers parked outside the mosque stayed, he added, “they would have all been killed.”

The peacekeepers’ capacity to respond to major attacks is compromised by CAR’s vast, often inaccessible terrain. After the attack in Bangassou, it took four months for additional soldiers and all their equipment to join the Moroccan contingent by what passes for road. Often, said MINUSCA’s Senegalese force commander, Lieutenant General Balla Keita, a clash is “already over before you get there”.

Last November, the UN Security Council approved a resolution to send an additional 900 peacekeepers to CAR. The troops were expected to include a battalion of 750 Brazilians with attack helicopters and other specialised equipment, and a company of 250 Rwandans.

But the deployment of the additional peacekeepers has faced repeated delays; politicians in Brazil are questioning whether its soldiers should deploy to a peacekeeping mission in Africa while the military is conducting its own operations in the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. IRIN understands that a decision on their deployment has now been deferred to October, at the earliest.

Meanwhile, over 400 Gabonese troops were repatriated in March following a string of sexual exploitation and abuse allegations. The battalion had been serving as MINUSCA’s emergency unit in Bangui, intended for rapid response to fast-deteriorating situations.

“We are at a point now where there are less troops than there were at the time when the [Security] Council mandated additional capacity last year,” said Cinq-Mars.

Where peacekeepers are the target

The man in charge of Bangassou’s self-defence militia has a no-picture policy. He said his special powers will crack camera screens. The more likely reason is that he is a wanted man. On the front of the UN tanks driven by Moroccan peacekeepers is a piece of laminated paper with his name – Giscard Larmassoun – and a black silhouette where his face should be. On the top of the paper is written “Fiche de Recherchés”: wanted list.

In a rare interview in March, Larmassoun said the ex-Séléka and so-called “mercenaries” hiding among displaced Muslims were his main concern. “We want to chase the Séléka away from this prefecture,” he said. “Our group is not against the government.”

But Bangassou’s self-defence group is wanted not only for violence against the Muslim community. They are wanted for a series of deadly attacks against peacekeepers, which could constitute war crimes under international law.

In 2017, 13 peacekeepers were killed in CAR, more than any year since the mission deployed. Three troops have also been killed since the beginning of this year, with the latest fatality occurring last Thursday. Bangassou and the surrounding area is the most dangerous of all. The nine fatalities there have forced the UN to fight two sometimes competing battles: one to keep the peace, another to protect itself.

Much of the self-defence group’s animosity toward MINUSCA centres on a single, crude belief: that the Moroccan battalion is from a Muslim-majority country and thus must be in cahoots with ex-Séléka groups, particularly the UPC.

Sitting in a house in Bangassou guarded by children with hunting rifles and machetes, Larmassoun, his spokesperson Yvou Walak, and a self-declared local sultan called Hervé Madanbari reeled off a series of provocative allegations against the Moroccan peacekeeping contingent.

The Moroccans distributed guns to the town’s Muslim population in the run-up to the attack last May, they said, and transported Muslims from the displacement camp into the town to attack a local priest. In nearby Rafai, the three men continued, the Moroccan mission provides the UPC with guns, ammunition, and logistical support. In Yogofongo – where a MINUSCA convoy was ambushed by the militia last May, killing four peacekeepers injuring eight – UN flak-jackets were found on the corpses of UPC fighters.

Accusations of bias against international troops in CAR are nothing new. But the rumours and misinformation against MINUSCA’s Moroccan battalion in the southeast is leading to levels of violence against the mission not seen before.

“MINUSCA is the boss of the UPC,” said Walak confidently, an automatic weapon in his arms. “If we meet them together, we will shoot on all of them.”

The self-declared sultan, who is named by the UN’s Panel of Experts in CAR for his role in supporting the militia, issued an even more chilling warning: “The Moroccans need to pay attention,” he said. “Or they will all die here.”

Confronting militia

Rosevel Pierre Louis, the UN’s top official in Bangassou, has little time for the rumours spread by the militia. “They have no evidence,” said the 49-year-old Haitian, sitting in a small, air-conditioned container at the UN’s base in Bangassou. “They are just trying to attack the credibility of the mission because we are protecting the IDPs [internally displaced persons] they came to destroy.”

For Louis, the reason the Moroccans continue to be targeted has less to do with their Muslim faith and more to do with their “posture” as a force. When UN peacekeepers in the country are attacked, he said, the rebels responsible should expect an immediate reaction: “You stay, fight back, control the area, and search for the perpetrators,” he said.

In Bangassou, this rarely seems to happen. The responsibility lies partly with the Moroccans, partly with the fact that MINUSCA has few troops at its disposal. But, for Louis, the problem goes much deeper than one battalion or even one peacekeeping mission.

“We don’t strike first,” said Louis. “That is the philosophy of peacekeeping, but the level of the threat has changed. Before, you had the flag and UN symbol and everybody respected it. Now, you are the primary target.”

Some missions have begun to strike first. In the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mali the UN increasingly functions as a direct combatant, with a mandate to proactively target armed groups and “enforce” peace.

If and when the 900 new peacekeepers arrive in CAR, some hope MINUSCA will be able to do the same. Onanga-Anyanga said the troops will come with “a combat spirit” and a clear objective to “change conflict dynamics”.

Keita said they will be divided into two separate battle groups: one based in Bambari, with a remit to control the southeast; the other in Bria, with a brief to stabilise the strategic town and then push towards other highly populated areas.

“I have to push out armed groups and make safe, and secure, areas,” said a bullish Keita. “This is what the new troops will be doing.”

But recent events in Bangui show just how difficult “pushing out” armed groups can be.

The mission’s attempt last month to dismantle a so-called self-defence militia (interviewed by IRIN last year) in Bangui’s Muslim enclave, PK5, led to some of the worst violence in the capital for years. Residents blamed the UN for firing on civilians and laid out 17 corpses in front of the mission’s headquarters.

An attack by the same militia earlier this month on a Bangui church left 16 dead and 99 injured, according to the Central African Red Cross, leading to fears of escalating inter-communal violence. Meanwhile, hundreds of ex-Séléka troops have gathered in Kaga-Bandoro, 330 kilometres north of the capital, to discuss an offensive on Bangui, citing violence in PK5 as the trigger.

Similar operations in places like Bangassou may have similar consequences. Like most self-defence groups, the fighters in Bangassou mix with the local population. Many are from the town. While some local residents may support their removal, “if we kick them out, we have to bear in mind that civilians will be killed,” said Louis.

In MINUSCA’s model town, a fragile peace

For an example of how to successfully push out armed groups, MINUSCA points to Bambari, the second-largest town in the country.

In February 2017, the mission dislodged UPC leader Ali Darassa from his stronghold in the town alongside anti-balaka leaders. MINUSCA’s aim was to prevent open fighting with a rival ex-Séléka group, the Popular Front for the Renaissance of the Central African Republic (FPRC), which was advancing in Bambari’s direction, primarily to target Darassa.

More than a year on, much has changed in the city. The backyard of Darassa’s headquarters is now occupied by a family displaced from a nearby town. His fighters, who once prowled the streets in uniform, are no longer visible. Neither are the anti-balaka. In their place are UN troops and police, and Central African gendarmerie.

“We are now in charge of the town,” said Alain Sitchet, the UN’s head of office in Bambari.

Thanks to the relative peace, humanitarians are now returning. In the central market, trade is brisk. On the bridge over the River Ouaka that demarcates Bambari’s Christian and Muslim communities, there is only a small UN presence. Before a sudden flare-up earlier this month, there had been no inter-communal violence for over a year.

“Our [Muslim and Christian] children are going to the same schools; they are being treated in the same hospitals,” said Janu Nguerendji, a pastor and member of a local peace and reconciliation committee.

But beneath the surface, peace in the UN’s model town is more fragile than it looks – as the recent up-tick in violence has shown. In press releases, the mission refers to Bambari as an “armed group-free town”. At MINUSCA’s field office, Sitchet prefers the more modest “armed group leader-free town”.

“What we don’t want to see in Bambari is people roaming around officially with their weapons and uniforms,” he said. “They cannot create illegal structures, detentions cells, police stations. They cannot play the role of the state.”

That is probably an optimistic description. A dozen or so former UPC combatants have found a new home in the administrative building of a local cattle market just three kilometres from the town centre.

The former combatants – as they defined themselves – were keen to downplay their past. Most had swapped fatigues for football tops. A chalk board on the wall was inscribed with CAR’s national anthem. The former fighters said they were teaching children the words.

“We don’t consider ourselves UPC,” said 24-year-old Mohamed Ib, wearing an Atlético Madrid top, jeans, and open sandals. “We are just citizens.”

But not everyone is convinced. Cattle traders say the ex-combatants are taxing sellers and buyers between 25,000 and 30,000 CFA ($45-$55) per animal. Traders complain they are running a protection racket in the town centre. Some say the money is being sent straight to Darassa, who still considers Bambari his headquarters. Almost everybody agrees the combatants are still armed, with a string of violent robberies and a recent attack on a police and gendarmerie base attributed to them.

As long as the UPC are present, the anti-balaka will be too. Sitchet insisted no armed groups have leaders, but “Waki”, a self-declared anti-balaka leader, and his deputy, “Colonel” Gervais Ramassani, were easy to find in Bambari’s Kidikra neighbourhood. They said their role is to stop fighters from using their weapons but, with the UPC still armed and capable of serious violence, they accept this can be hard to enforce.

“There are many that still have guns,” said Ramassani. “If something happens, they will act.”

“It will take 40 years”

The challenge of genuinely removing armed groups is matched only by the challenge of restoring the CAR government. MINUSCA’s exit strategy will ultimately depend upon creating functioning state institutions in areas like Bambari, where they take control from armed groups.

But in a country with little history of effective central government, this is easier said than done. In Bambari, dozens of civil servants sent from Bangui over the past few months have gone back to the capital, citing irregular salary payments and poor accommodation.

“It is a permanent struggle to keep them here,” said Sitchet.

The UN Development Programme has been rehabilitating state buildings, but support from the government is lacking. Inside a police station, Emmanuel Gbomon, the commander of a new unit sent to Bambari last December, was working in almost total darkness. The solar panels fitted by MINUSCA were broken. There was no money to fix them. The commander sat, bent awkwardly, over a tiny desk tucked away in the corner of a large but empty room.

“This is my office,” he laughed.

Down the road, at a gendarmerie base, a commander who asked not to be named said the unit had too few vehicles and weapons, no functioning radios, no electricity, and no generators.

“When we go on patrols, we always have the support of the UN,” he said. “We cannot go out alone.”

With the state struggling to redeploy in Bambari, there is a danger the mission may have to take over even more state functions if it wishes to replicate the armed group-free model elsewhere.

“If you cannot fill the vacuum, then you will be creating another problem for yourself,” Keita, the Senegalese force commander, admitted. “That is why we are waiting for the new troops to come.”

But even if the 900 new troops do arrive, Onanga-Anyanga accepts that regaining “spaces of law and order” will take time. “A chaque jour suffit sa peine,” he said, turning to a biblical proverb that translates roughly as, “Take each day as it comes.”

“In a process where [statebuilding] is incrementally done based on established rules and good, responsible governance, it takes 40 years,” he said.

In Bangassou, the Muslim community cannot wait that long. The pattern of inter-communal violence that has ravaged various parts of this country for five long years is becoming increasingly evident there.

Rumours were spreading of an imminent attack from the largely Muslim UPC fighters in nearby Rafai. At the camp in the Catholic church where the town’s Muslims now live, additional peacekeepers deployed to protect the community from Larmassoun’s men struggled to stem a daily tide of violence.

On a recent Friday afternoon, a 15-year-old Muslim boy was decapitated after leaving the camp to search for firewood. His severed head was found by UN peacekeepers, rotting on the northern bank of the Mbomou River.

The boy’s father, Sallet Saidou, said he wants the government to escort the rest of his family to somewhere safe. But patience is now running thin in a war with no clear end.

“Tomorrow, we will have to fight,” Saidou said.

Read part 2

pk/ag