“My apologies, I have to go,” Khalid al-Shimari proffers as he races to his car, gravel scrunching under his feet. In the pocket of his blazer a ringtone sounds for the umpteenth time. “My court needs me,” he explains, pulling open the car door. His driver accelerates away.

Al-Shimari, 47, is a judge. Having just handled a host of important administrative tasks, he is speeding out of Chamakor, a camp for displaced Iraqis some 40 kilometres east of the recently liberated city of Mosul.

Since so-called Islamic State took over Mosul in June 2014, his court has operated out of the nearby district of Hamdaniya. Not only is al-Shimari a judge in exile and an internally displaced person himself, but since December he is also one of Iraq’s most in-demand professionals: a mobile magistrate.

Every Thursday, al-Shimari, who has worked for the provincial court for 14 years, visits one of the IDP camps around Mosul to hold court sessions and register marriages, births, and other important life events.

A meeting with al-Shimari is a godsend for those among the tens of thousands of Iraqis who (after three years of war) no longer hold things like ID cards and birth certificates.

In Iraq, this is not just a matter of record. The absence of key documents can prevent IDPs from passing checkpoints and accessing public services, even from receiving vital humanitarian aid.

There is plenty of work to do. Some have lost or damaged their papers amid the chaos of conflict. Others couldn’t renew them in time or hold documents issued by IS that aren’t recognised by the Iraqi government.

But, as more and more parts of the country are liberated from IS, the trips al-Shimari and a colleague are making are hardly making a dent in one of Iraq’s greatest challenges. “It is a disaster,” said the judge of the administrative mess.

Mobile court

The idea of a mobile court came from the UN’s refugee agency, UNHCR, and the Swedish NGO Qandil.

UNHCR estimates that the average family displaced from Mosul is missing two to three key documents. In five camps alone – currently home to more than 70,000 IDPs – Qandil has identified as many as 31,481 missing documents.

According to a report by the International Organisation for Migration, 88 percent of Iraq’s three million IDPs said the challenges around missing documents are one of their major concerns.

Iraq’s justice system, already slow, is now even further weighed down with a document backlog that is hindering displaced Iraqis with lengthy procedures that can delay any chance of them getting their lives back on track.

“The system can be cumbersome and time-consuming,” said Leila Jane Nassif, UNHCR’s deputy representative in Iraq. But this seems like gross understatement when al-Shimari lays bare his workload, which goes far beyond matters of documentation: “It is horrible,” he told IRIN. “There were times where my own court dealt with 500 cases a day.”

Making matters worse, most displaced people who reside in camps in the Kurdistan Regional Government-controlled areas are not allowed to leave the site for security reasons without special permission, preventing them from even accessing the courts or civil affairs offices.

The call to action was clear for UNHCR, explained Nassif: “[Aid organisations] needed to work with the courts to help them find new ways to deal with the large backlog of cases.”

And so, together with Qandil, the UN-agency reasoned: if you can’t come to the judge, we will bring the judge to you.

Too much demand

In addition to al-Shimari, there is only one other mobile judge in the area, although there are a few other NGOs working on similar issues.

On the day IRIN tagged along, al-Shimari was forced to leave Chamakor and his notary and legal team prematurely, two hours earlier than planned. The reason? Two alleged IS fighters were awaiting trial at his court in exile in Hamdaniya. He was required to adjudicate.

“And now what?” asked Ghazi, a civilian resident of west Mosul left standing forlornly in front of Qandil’s white caravan office at Chamakor after al-Shimari had departed.

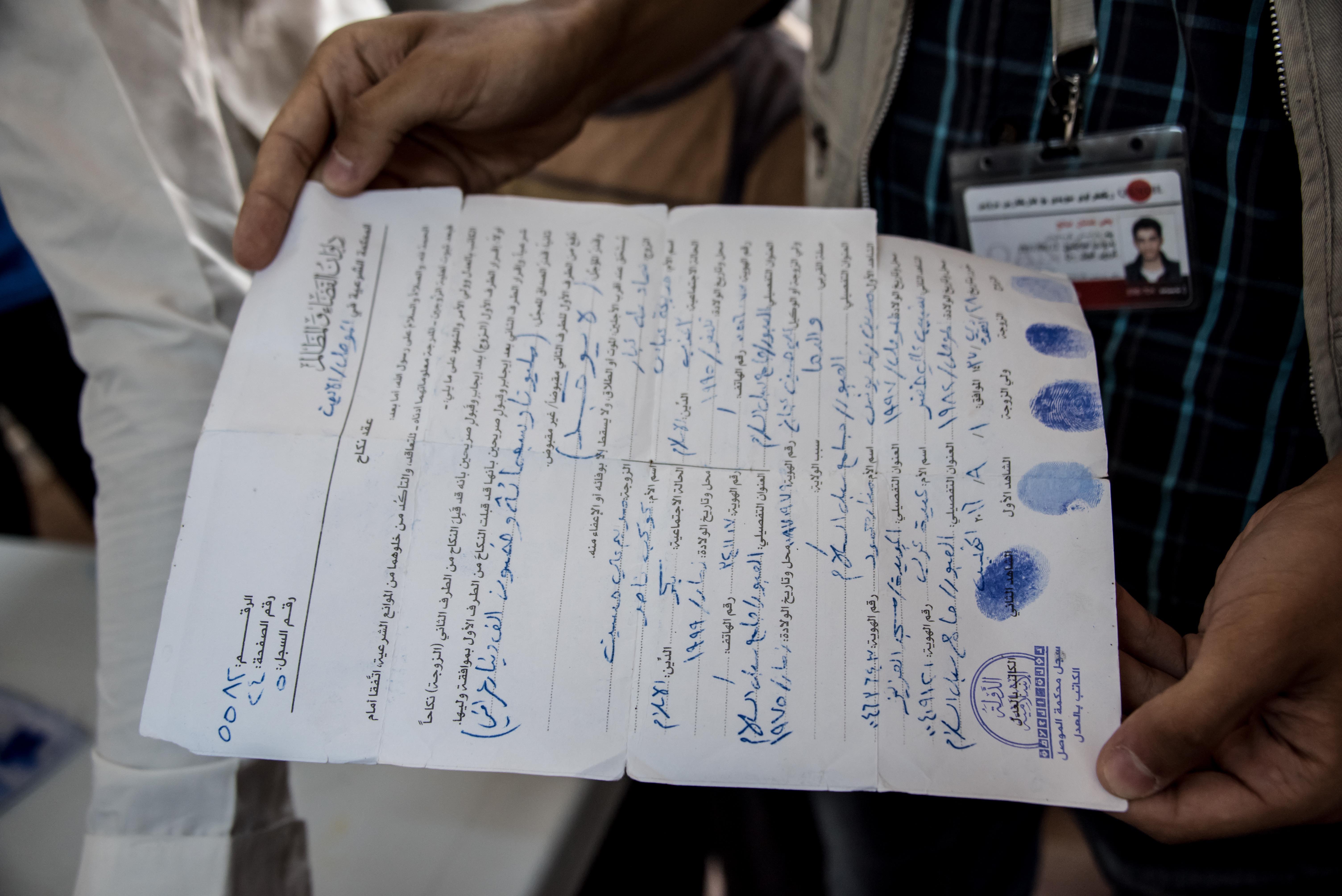

Ghazi had been waiting to change his IS-issued marriage certificate for a legal one issued by the Iraqi government. He would now have to wait another two to three weeks for al-Shimari to return to Chamakor.

And transferring his marriage certificate was only the first of many bureaucratic steps that lay ahead. He then had to register his two toddlers, born in Mosul during the past two years. But this couldn’t be done without a valid marriage certificate. He also couldn’t update the status of his government-issued identity card from “single” to “married” without a marriage certificate as this required a trip to one of the civil affairs offices based outside the camp.

“We can’t leave, so that will be difficult,” said Ghazi, grimly.

Next to him stood Jasim, a middle-aged man with a red and white traditional headscarf. He heaved a deep sigh. “Daesh [IS] burnt down my house, including my personal documents,” he told IRIN.

Jasim was after a marriage certificate to register his household at the Iraqi Ministry of Trade, a step needed to register for monthly aid distributions from both UN agencies and the Iraqi government. “All these papers, I find it too complicated,” he mumbled.

It’s unlikely that Jasim will be served by al-Shimari any time soon either as the waiting period for a session with the mobile judge is currently three months.

With the help of Qandil’s legal team, al-Shimari and the other mobile judge have settled 387 cases since December 2016.

But this is just the tip of the iceberg and Aram Mahmood, a legal aid worker at Qandil, told IRIN that speeding things up is simply not an option at the moment.

“We would like to set up a full-time court in the camps, but the high council for judges in Baghdad has not honoured that request yet,” he said.

UNHCR and Qandil have also asked Iraqi courts to approve documentation applications in bulk instead of dealing with individual cases.

As negotiations on these changes continue, the IDPs have to simply take what they can get: visits once a week, one judge, in just one of the five selected camps.

Newlyweds

Zyad, 26, and Hadeel, 20, were one of the lucky couples al-Shimari did have time to put on the marriage registry that day.

Together with their 18-month-old daughter Noor, the newlyweds – from the town of Zummar, some 60 kilometres west of Mosul – have been living in Chamakor since April.

They were first married in a religious ceremony in August 2014, a month after IS took control of the town. The family celebrated the unofficial wedding out of sight of the extremists, and pictures of the clandestine party were now safely tucked away in a plastic wallet back in the tent they called home.

Receiving a state marriage certificate was certainly a relief for the young family, but it didn’t solve all their problems: After routing IS, Kurdish forces took control of Zummar. “We are told we are not allowed to go back,” explained Zyad.

If Zummar becomes part of Iraq’s autonomous Kurdish-controlled region, there may yet be more paperwork for them to come. “That is something to be thought of later,” said Zyad. “First things first: register our daughter.”

TOP PHOTO: Jasim remonstrates with a mobile court official over his lack of a marriage certificate, which is hindering his right to register his family for aid distributions. Elizabeth Fitt/IRIN)

eh/as/ag