Three years on from the start of the West African Ebola epidemic, lessons are still being learned. And the most surprising are not coming from the scientists, but from the affected communities themselves; about how, with hardly any help, they tackled the virus and won.

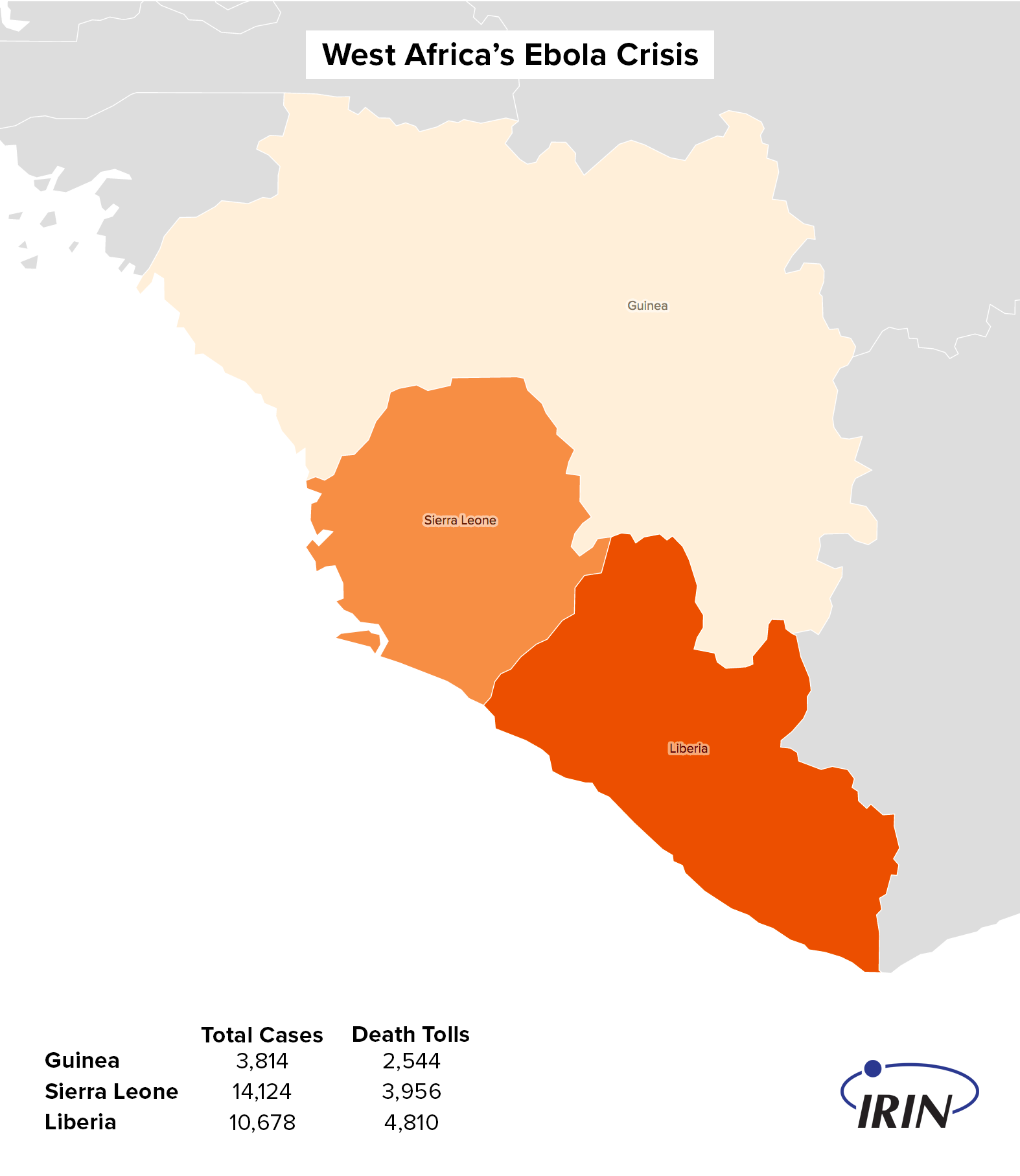

One of the curious aspects of the epidemic, which shook Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, was the way in which the number of cases started dropping before the main international response was in place. In one area after another, the infection arrived, spread rapidly, and then – apparently spontaneously – began to decline.

Ebola first crossed over from Guinea into Liberia's Lofa County in March 2014. A rapidly erected treatment centre at Foya, on the border, was soon full to overflowing. In September, it was treating more than 70 patients at a time. But by late October, the centre was empty.

People’s science

Paul Richards, a veteran British anthropologist, now teaching at Njala University in Sierra Leone, has been worrying away at this phenomenon. He is convinced the main driver of the reduction was what he calls “People's Science”; the fact that people in the affected areas used their experience and common sense to figure out what was happening, and began to change their behaviour accordingly.

He told a recent meeting at London's Chatham House: “One of the pieces of evidence which makes me think that local response was significant is that the decline first occurred where the epidemic began, so that the longer the experience you had of the disease, the more likely you are to see tumbling numbers. So, someone was learning… People ask me, 'How long does it take to learn?' And we don't know, but on the basis of this case study, it's about six weeks.”

A lot of national and international effort was put into public health education, and the messages broadcast on radio were very widely heard. But initially they were not very helpful, with a lot of emphasis on the origin of the disease, and warnings not to handle dead animals or eat bushmeat.

In fact, it now seems likely that only the very first case came from a wild animal; all subsequent cases were caused by human-to-human transmission.

The villagers interviewed by Richards and his team were sceptical about the government’s warnings: “If eating bushmeat is dangerous, why did no one get ill before”, was a typical question raised.

He found the conclusions they drew from their own observation and experience were much nearer the mark.

“We know our own people,” they told him. “So, we know that it’s socially obligatory to wash the bodies of dead people and to attend their funerals. We monitor very closely who's not doing that, who's not paying attention to their social duties.

“So, it very quickly dawned on us that the people who were attending funerals were the ones that were dying, the good people, the ones that do their social duty,” Richards recounted. “So, from that we knew that it was something to do with funerals and we started modifying our behaviour.”

Getting organised

The areas where Richards was working in Sierra Leone had been badly affected by the civil war. But that period had taught them how to organise, and how to depend on their own resources. The Kamajor civil defence groups, which had protected villages from the notoriously brutal RUF rebels, were revived as taskforces to track cases, enforce quarantine, and bury bodies safely.

Across the border in Liberia, the same thing was happening. Nyewolihun, a small village in the forest, not far from the original source of the outbreak, put itself into quarantine.

Matthew Ndorleh, the headmaster of the local school, told IRIN: “We didn't allow anyone to go and sleep in any other place, and we didn't allow anyone to come in. We set up a taskforce of young men to man checkpoints at all the entrances to the village, and everyone obeyed it.”

It was hard, and having to rely on its own resources meant the village ran short of rice, but although Ebola reached the nearby town of Kolahun, Nyewolihun stayed safe.

It is clear that one of the missed opportunities in the outbreak was a failure to encourage these local initiatives and give local people the tools and techniques they needed to do the job.

Governments and aid agencies preferred to recruit and train official burial teams rather than teaching people how to bury their own dead safely. But there were numerous complaints about difficulties in contacting these teams, long delays, and disrespectful attitudes to the deceased. More isolated communities had no alternative but to take care of their own dead, whether they were trained and equipped or not.

DIY response

American anthropologists, who interviewed people in urban areas of Liberia during the outbreak, found a sense of frustration that the information campaigns told them about the origin of Ebola, how it was spread, but didn't give them practical advice on how to care for sick relatives, how to transport them safely to hospital, and what to do with corpses when the burial teams didn't arrive.

They wanted training, and they wanted access to protective equipment. “We have heard the messages,” said one interviewee, “but most people do not know how to practicalise them.”

This was because Ebola is such a dangerous disease that home nursing, the transport of the sick, and do-it-yourself burials were being strongly discouraged. It took six months for Sierra Leone to finally produce a poster giving some advice on caring for the sick, and even then it was headlined, “Taking Care of Someone with Suspected Ebola: Be Safe While You Wait”. The clear message was that this was only a stopgap – professional care had to be the norm.

And yet, in reality, people did have to take care of Ebola patients at home. The early stages of the disease are not obviously different from any other fever, and so would be nursed in the usual way. Once Ebola became obvious, patients were sometimes too sick to be safely moved, especially from off-road villages where the only form of patient transport was a hammock.

Richards met communities that had worked out the dangers of hammock transport for themselves, without it having been mentioned in official health messaging.

Care in the community

Some patients were kept at home because they and their families were terrified of the big Ebola treatment centres, where patients, once taken away, disappeared behind high fences and were often never seen again.

“They would transport you from your village to Freetown. You had never been to Freetown, never seen these town places,” explained Esther Mokuwa, who worked with Richards on his study. She was told by patients: “If you take me from my loved ones, even the discouragement would kill me.”

Mokuwa said the Community Care Centres that were eventually constructed in late 2014, although modest, were much more acceptable.

“People could go there; they had their colleagues working inside who could take messages; so they could relax. At the CCC, even though you were very safe, you could see them, and even stand talking. You could cook food and bring to them in the centre. Like pepper soup – pepper soup is very important in [West] Africa!”

This was much more like normal care. People finally had a way to express their love and support, and do what they considered the proper thing for their loved ones.

The team investigating urban attitudes in Liberia met women who had planned in advance what they would do if anyone in their family became infected, and had worked out how they could nurse them as safely as possible. Many had seen the news reports of a student nurse who improvised protective kit from plastic bags and bin liners – and successfully nursed several family members without becoming sick herself – and were thinking how they might do the same.

With hindsight, it might have been wiser to acknowledge these powerful and understandable emotions, and the practical difficulties of providing professional Ebola services in remote areas, and to place more trust in the communities who wanted their own training and equipment.

But at the height of the epidemic there was no time to have a debate about community action and how best to harness it. The hope now is that the work being done can inform future policy, should another deadly epidemic emerge.

eb/oa/ag

TOP PHOTO: Community volunteers in Liberia. CREDIT: Morgana Wingard/UNDP

MAP SOURCE: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/IRIN